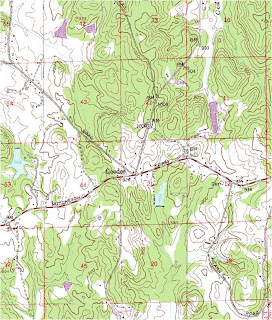

After all the visitor conveniences of Etowah Indian Mounds (museum, gift shop -- and yes, I bought another book there, videos, interpretive brochure), McIntosh Reserve is a bit of a shock. The main feature of the park is the grave of Chief William McIntosh: a stone that looks like a turtle when viewed from the right angle, and like a granite boulder covered with colorful lichens when viewed from every other angle; a small gravestone, a later addition, with his name, dates of birth and death, and military rank; and a state historic marker. After signing the Treaty of Indian Springs (identified in a smaller historic marker sign across the road), McIntosh retired to his "Reserve", a square mile set aside for him for the rest of his life, the smallest fragment of the expanse of Creek territory that he relinquished to the whites. He received, too, a large sum of money, but he did not enjoy the money or the Reserve very long, before he was assassinated (or justly executed?) by a band of Creeks opposed to the treaty (which was practically everyone else in the tribe). When he was killed, his home and all his outbuildings were burned, but the money he received as part of the treaty was never recovered. Legends have it that it may be buried somewhere in a parish in Louisiana....

Here, then, is McIntosh's gravestone, in two views. If you squint just right at the lower picture, you might imagine the carapace of a turtle.

Across the road stands a dogtrot home, about the same age as, and similar in appearance to, the house McIntosh lived in. This one was moved from somewhere in Alabama and rebuilt at the Reserve about ten years ago. Several of the rooms are open, but unfurnished apart from an out-of-place ugly upholstered chair. Beyond the house, the land drops away sharply, toward the floodplains of the Chattahoochee River. It was there that the Creek Indians would have their Green Corn dances. But on the day of our visit, the space was in use, instead, by a couple of people flying their remote-controlled model airplanes.

After a short visit to the floodplain (where Carole regaled us with accounts of her family's settlement of the area, and spoke of how many of her Lassiter relatives are buried in a cemetery that is now surrounded by private land), we started on our way out of the park. On the way, we stopped at an old graveyard that had been next to a church once, a ways back. The graveyard supposedly contains the graves of McIntosh's wife, Senoia, and one of his three wives. We scrutinized the gravestones, but most were too worn to be legible. All around us, in the woods, were lines of rock, pretty pink gneisses and yellow-brown chunks of quartite, probably marking out family burial plots. Carole speculated that hundreds of people might in fact be buried there. A peaceful spot.

I think I was more intent on the rocks than the graves, though. My wife Valerie found a weathered piece of gneiss containing red-brown lumps that were likely garnets. I almost carried it away with me, but could not bring myself to desecrate a cemetery by removing it. The rock colors were enchanting, though. Valerie captured the soft tones of the rock (justaposed by the green-gray of a shield lichen) in the photograph below:

On the way home, I felt the thrill of realizing how many places I still did not know about, and stories I had not yet encountered, in and around the Chattahoochee Hill Country. We passed another unkempt graveyard along Highway 70 -- a few stones among the trees at the side of the road. I imagined projects, perhaps with Montessori school students, of clearing off the stones, doing rubbings, perhaps even researching the people that were buried there....

The Hill Country landscape, full of fragments of memory in metal, stone, and wood, beckons to me, calling me closer.